June, 1968, I was living in Buenos Aires with Patrick, an Anglo-Argentine businessman whose passion was poetry. In the daylight hours, he was a senior executive at a foodstuffs conglomerate known especially for its English-style mustard. At night, and on weekends, he wrote sonnets and villanelles, many of which were published in literary journals in England. I thought that Patrick should experiment with free verse, and told him so, but he did not depart from meter and rhyme.

Even though I had won a minor U.S. poetry contest, my own efforts were mostly being rejected, but Patrick admired the energy of my poems. I was inspired by walking urban streets and by the lives of poets who had committed suicide. Patrick and I didn’t copy each other’s styles. We delighted in each other, but I can’t say it was love—at least, not from my side.

I can’t remember whether it was Patrick or I who first got the idea that we should have Pablo Neruda write an introduction to a joint collection of our poems. We were fearless and convinced that our poems merited the great poet’s benediction. My plan was to show up at Neruda’s doorstep, in Chile, and wing it. Patrick drove me to the airport and I flew to Santiago, a short hop of slightly more than two hours. From Santiago, I took a sixty-mile bus trip west to Isla Negra, where Neruda lived in a house by the Pacific Ocean. I was greeted at the door by Matilde, his wife. In my limited Spanish, I introduced myself as an American poet who had long admired Neruda. Would it be possible to meet him? Matilde informed me that he was not home; he had gone to a nearby quarry—his morning routine—to watch the workers excavate stone. She invited me to come back at one o’clock for lunch.

Nervous and excited, I spent the intervening hour walking aimlessly on Isla Negra’s rural roads. Though it was not actually an island, Neruda himself had christened the area “Isla” for its isolation and “Negra” for the dark outcrop of rocks just offshore. When I returned, promptly at one, Neruda (a burly man with an expression of inquiry on his face), Matilde, and a young woman were sitting at a round dining table. A place had been set for me. Neruda introduced me to the young woman, Teresa Castro, his literary secretary. A maid served us a four-course meal; I recall the main dish, a delicious fresh-caught salmon. After every course, Neruda ate several sardines as a condiment. This was his custom, his palate cleanser. The sardines rested, shiny and fresh, on a small plate, waiting to be demolished.

Third wives, in my experience, can be insecure. Although Neruda and Teresa spoke English, Matilde, his third wife, did not. To include her in the lunch conversation, and to put her mind at ease that I wasn’t there to steal her husband, I spoke Portuguese (I had lived in Brazil for the previous year) while Neruda, Matilde, and Teresa spoke Spanish. We understood each other, more or less.

We talked about my government’s refusal to let Neruda enter the U.S. As a member of the Chilean Communist Party, he could not get a visa. He was incensed. He had many admirers in the United States and invitations from prestigious institutions to give readings. He remembered fondly the one time he had been allowed to visit, when the playwright Arthur Miller prevailed upon the Johnson Administration to let him attend a congress sponsored by penInternational, in New York City, in 1966. Neruda and I talked about his career in Chile’s diplomatic service—postings in Burma, Mexico, Spain—and the abundance of objects and trinkets that filled his house. He said he couldn’t live without being surrounded by his “toys,” big and small. Finally, I broached the reason for my visit. Would he read a few of the poems that I had brought with me? To my delight, he said that after lunch he would take his customary nap and after that he would read our poems. If he liked them, he would write something for our book.

While Neruda napped, Teresa gave me a tour of the house, which, viewed from the outside, looked like a houseboat with random additions. Inside, it was crammed with collections of all sorts. Neruda’s obsession with the sea was on display everywhere. Hundreds of seashells lined the bookshelves and covered every tabletop. There were nautical instruments, ships in bottles, paintings of ships, teeth from sperm whales. Teresa told me the names of some of the figureheads—Jenny Lind, La Novia, Medusa—women carved in wood, in contact with the sea but oblivious to its dangers.

Teresa and I were close in age; we bonded easily. At around four o’clock, Neruda summoned Teresa to give her a poem he had written for Patrick and me. He had liked our poems! I read his typewritten poem with trembling hands. It would work perfectly for our book.

I conveyed my thanks, through Teresa, and she walked me to the bus stop for my return to Santiago. On the highway, a young man, also waiting for the bus, was listening to a news report on a transistor radio. I caught the words “Robert Kennedy” and “disparo!” Bobby Kennedy had been shot in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel, in Los Angeles. He had undergone extensive neurosurgery, but he was not improving. I felt desperately far from home and wished that I could be with Americans.

When I arrived at my hotel in Santiago, that evening, Kennedy was still fighting for his life. Feeling vulnerable, I made a last-minute decision. Rather than fly back over the Andes, I would take a colectivo (jitney) through a pass in the mountain range to the Argentine city of Mendoza and fly the last leg of the trip, from Mendoza to Buenos Aires.

The following morning, I shared the back seat of the colectivo with a middle-aged man. A middle-aged woman sat in front with the driver. During the entire trip of nearly five hours, she talked loudly to the driver about how she was going to show up in Mendoza unannounced, surprise her good-for-nothing husband, and catch him with his new girlfriend. Her fury was boundless. She didn’t stop her tirade even when the driver had to negotiate patches of snow at the summit of the pass.

As soon as the colectivo arrived in downtown Mendoza, the woman screamed at the driver to stop. Then she leapt out, ran up to a couple holding hands as they walked along the street, pulled a knife out of her purse, and plunged it into the man’s back. For a few seconds, the three of us in the colectivo were frozen in our seats. The two women screamed at each other while the man lay bleeding on the sidewalk. Then the driver, my fellow-passenger, and I jumped out of the vehicle. Pedestrians stared in disbelief. The wife shouted, “This is my husband, the adulterer! I hope he dies! Taking up with this tart, he deserves it!” The other woman yelled back what I took to be obscenities.

It didn’t take long for the police and an ambulance to arrive. The jealous wife was escorted away, and her husband, still alive, was put on a stretcher and driven off in the ambulance with its siren blaring. Two policemen stayed behind to question the onlookers.

Walking away from the crime scene, I passed a kiosk and saw the newspaper headline. Bobby Kennedy had died overnight, twenty-six hours after he was shot. I bought a paper and read the full story. My flight to Buenos Aires wasn’t until early evening. Saddened, my nerves frayed, I decided to pass the time by going to the movies. “Bonnie and Clyde” was the only movie playing that had an English soundtrack. I wasn’t in the mood for more violence, but I went to the film anyway. Afterward, I found a taxi to take me to the Mendoza airport.

As I stood in line to purchase my ticket to Buenos Aires on Aerolíneas Argentinas, I heard American English spoken behind me. I turned to see two young men in dark business suits. Hoping to tell them what I had witnessed that afternoon and to talk about the tragic news of Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, I suggested we go to the airport lounge for a drink. At the bar, I ordered a double Scotch. Both men ordered orange juice. “I would feel safer if we were flying on an American airline,” I said. “Don’t you want something stronger?”

“No,” they said, in unison. One of the young men explained that they were Mormons and didn’t drink alcohol. I had never met a Mormon before and knew nothing about their prohibitions or their worldwide missionary activities. I was still outside my culture.

Patrick and I never finished our book. I left Buenos Aires some months later and didn’t return for twenty-two years until, in 1990, my husband and I had tea at our hotel with Patrick and his wife. Both Patrick and I thought that the poem Pablo Neruda wrote for us was lost. He couldn’t find his copy, and I couldn’t find mine.

Patrick died in 2003. In 2014, packing for a move, I found Neruda’s poem filed among my grade-school report cards. At almost the same time, the poem was discovered in Santiago, by the Neruda Foundation’s archivists.

Roa Lynn and Patrick Morgan

were moored in these waters,

bewildered on this river,

hostile, florid, morose,

they go off to sea or to hell,

with an intensifying love

that bathes them in light

or plucks them from the algae:

but the waters rush on

through darkness, full of voices,

a rhapsody of kisses and ashes,

streets bloodied by soldiers,

unacceptable reunions

of grief and blubbering:

so much carried by these waters!

our pace and place,

the ferment of the favelas

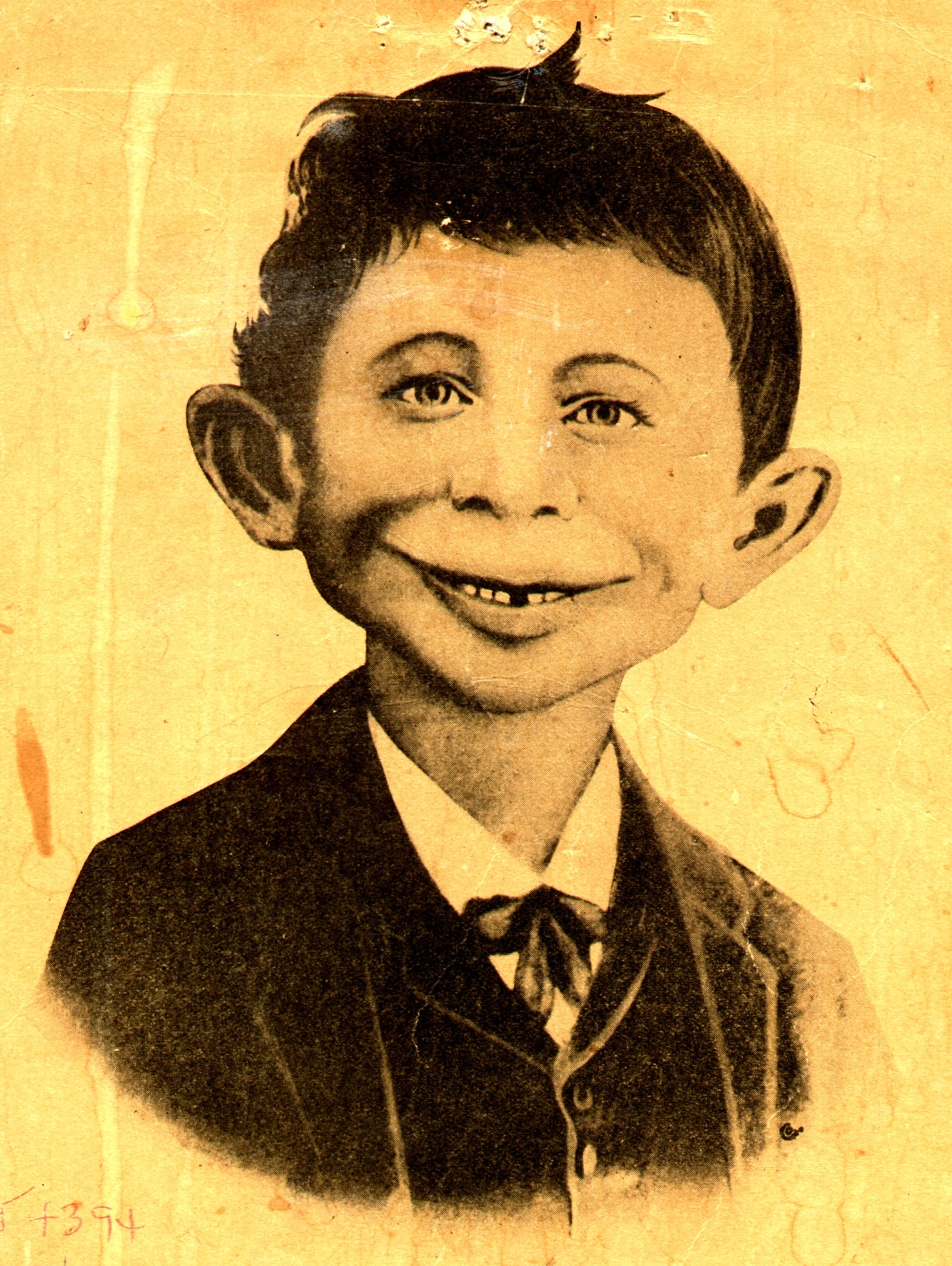

and ghoulish masks.

Just look what the water’s carrying

up this four-armed river!

“19” [“Roa Lynn and Patrick Morgan”], by Pablo Neruda, from “Then Come Back: The Lost Neruda Poems.” Copyright © 2016 by Fundacíon Pablo Neruda. Translation copyright © 2016 by Forrest Gander. Used with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of Copper Canyon Press.

(Originally Published at the NewYorker)